During the winter of 2014-15, Mac Baler ’15 used his AMS Grant to study the geography of youth language in Japan. Following Yanagita Kunio’s theory of “peripheral zones,” Baler wondered whether important cultural centers still drive the creation of new words, phrases, and dialects. “There are a few Japanese resources investigating youth language as a whole,” he wrote, “though one is pressed to find data cataloguing this youth language by region.” What follows is Baler’s report, detailing both his experience on the ground in Japan and some preliminary results.

This past winter break, through my AMS independent research grant, I was able to return to Japan to conduct linguistic surveys concerning the current state of, and dialectical variants on, Japanese youth language. Since the day I left Japan, at the end of my semester studying abroad at Kansai Gaidai University (関西外国語大学) in Osaka, Fall 2013, I vowed to return. I knew it wasn’t さようなら (sayonara), meaning goodbye, but, as youth would say, またね (mata ne), meaning, literally, “again, yeah?” – casual parting words between friends, akin to “see you later.” Even here, in the form of saying goodbye, youth language appears.

In my time studying abroad, I discovered the phenomenon of Japanese youth language, and the vast variety, and quick turnaround, it possesses. As my university pulls students from all over Japan, it became common to talk with friends about the Japanese slang or dialect used in their hometown, and vice-versa, as I was learning their language, and they learning mine. Upon returning to Colgate, I spent time pondering different possibilities for a thesis in Japanese, and in discussing possible books to translate with my Professor, my interest in youth language shone through, and a book titled 「若者言葉に耳をすませば」(“If We Lend An Ear To Youth Language”) came up. Upon reading through this book, I realized that there are those who are interested in these same kinds of language trends or word usage as I was, and that I could perhaps return to Japan and do some sort of survey on the current state of youth language, in comparison with this book’s results from 2007, focusing in on certain aspects I discovered in the book in which I had a particular interest. Simultaneously, I discovered that the Japanese Agency for Cultural Affairs does national public opinion polls on Japanese language and usage, showing even more native interest in such things. In these polls, and in the youth language book, there were bits touching on how such language varied by region. This particularly sparked my interest, and related directly to that which I experienced firsthand while studying abroad. The area in which I was, the Kansai region (south-central region of Japan’s main island), is famous for its dialect, which everyone in the nation knows, and through my interactions with students, my host family, etc., I was able to recognize it and pick it up. When talking with friends from Tokyo, across the country from Kansai, or looking at a textbook, such dialectical words did not appear. I therefore sought out to expand on these experiences I had while in Japan, and return, conducting surveys on Japanese youth language, and if, and if so, how, it changes depending on where you are in the country.

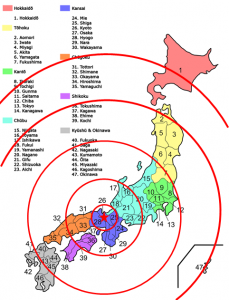

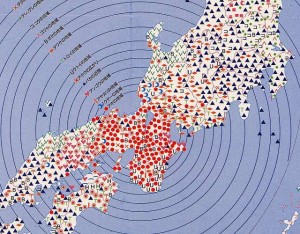

I find it necessary to give a brief background concerning Japanese trends and a bit of interesting yet informative history concerning the birth of certain geographic dialectical trends. In general, Japan is unbelievably trend-conscious, and fad-driven. Whether it be fashion, popular media, etc., youth are up with the trends. Furthermore, these trends are always in flux, changing unbelievably quickly. It turns out that these trends apply to youth language as well. As for dialects, there is a notably large number despite Japan’s size. Interestingly enough, they’re quite distinct from one another, yet their origin is often under debate. However, for linguists, one school of thought concerning the dissemination of dialects prevails. In the early 1900s, Yanagita Kunio, the father of Japanese folklore study, traveled throughout Japan, noting the different dialectical words for “snail” used throughout the country’s regions. He discovered that the distribution of these dialectical words formed concentric circles throughout the country, with their center/source point located at the nation’s former capital, Kyoto, in the Kansai region.

Centered at Kyoto, each consecutive ripple zone contained the same word for “snail,” and share similar language trends.

From this, he proposed his方言周圏論“Peripheral-zones Dialect Theory,” stating that synonyms or “buzz-words” are created in influential, cultural centers (i.e. the nation’s capital), and general propagate beyond, over time, extending out in a ripple-like fashion. This not only portrays the frequency with which slang words are created in Japan, so fast that words are rippling across the nation, but also how different the language can grow to be. This same ripple concept was the basis of a television segment and eventual book (1996), which charted what word people used to mean “fool” or “idiot,” focusing on two main words – baka, used often in standard “Tokyo” Japanese, and aho, a word seemingly of Kansai dialect. As expected, the results were a ripple, focused on the old capital of Kyoto in the Kansai Region, with similar words exiting in concentric circles disseminating outward.

Upon my discovering this survey, I remembered the frequent use of the word aho by my Japanese friends from Kansai, or by my host-family, but not by others from outside the region.

With this foundation in mind, I set out to create a survey asking people what kind of youth language they’re currently using, in aim to see not only the current state of youth language, in 2014/5, compared to that of prior years, but to also see if respondents’ answers would vary depending upon their birthplace / region in which they currently live. I therefore went to Japan over winter break, from late December to mid-January, spending a little less than a week in the Tokyo area, and almost two weeks in the Kansai region (Kyoto, Osaka, Nara, etc.), conducting my surveys. This was truly made possible via the help of contacts I had in Japan – Colgate alumni, prior Colgate language interns, my host family, and most of all, the various friends I made while studying abroad, with whom I had remained close.

As for the survey itself, I created one version that could be distributed in person, via paper, and online as well. I created some unique questions of my own, based some off of topics in the youth language book mentioned before, and mimicked some asked in the Japan Agency for Cultural Affairs national polls, to allow for the possibility of seeing a difference in results over time. The question types ranged from multiple choice (“Which of the following emphasis words do you use most often?”), to fill-ins (“If you had to pick a youth word you wish would go away/out of fashion, what would it be?”), to short answer (“Why do you think there is such variety in current youth language usage patterns?”), etc. I also asked birth location and current residential location in order to guarantee an accurate knowledge of participant geographical influence.

As for the survey itself, I created one version that could be distributed in person, via paper, and online as well. I created some unique questions of my own, based some off of topics in the youth language book mentioned before, and mimicked some asked in the Japan Agency for Cultural Affairs national polls, to allow for the possibility of seeing a difference in results over time. The question types ranged from multiple choice (“Which of the following emphasis words do you use most often?”), to fill-ins (“If you had to pick a youth word you wish would go away/out of fashion, what would it be?”), to short answer (“Why do you think there is such variety in current youth language usage patterns?”), etc. I also asked birth location and current residential location in order to guarantee an accurate knowledge of participant geographical influence.

Time for results! I was able to garner 97 responses in total. I’ll now provide a brief synopsis of the results or interesting takeaway from each question.

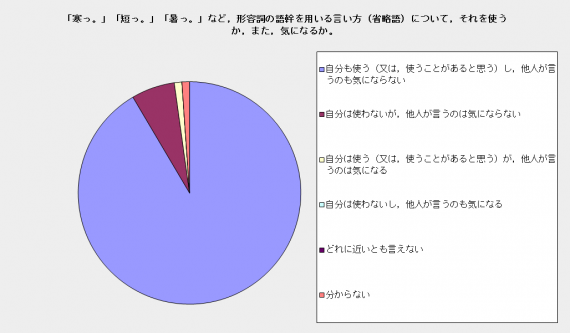

It turned out that a whopping 91.6% use shortened, abbreviated adjectival forms, and don’t mind when others use them either. Only a few said that they don’t use them, but don’t mind when others do, and only one person claimed to using them themselves, but admittedly caring when others do. This large majority that do use these stumped adjectival forms was not influenced by location – both in and outside of Kansai they are used. As for emphasis words, it was clear that meccha (“ridiculously”) took the cake, with a leading 42.3% of participants choosing it. Interestingly enough, though to not much surprise, 36 out of the 41 who chose meccha live in Kansai – this extreme usage was something I picked up on while at university there. Regarding imported words, two words pulled ahead – misuru, coming from “miss,” meaning to fail or not achieve, came in with 42.3%, and chekkusuru, coming from “check,” meaning to check or confirm, registered at 26.8%. Somewhat surprisingly, though, it seemed that 35 of the 41 who picked misuru were from Kansai, something I had not expected. I also asked whether one uses aho or baka, mimicking the survey done in the late nineties, mentioned above. As expected, the large majority who picked aho either currently live or were born in the Kansai area, and, in contrast, a large majority of those who picked baka live or were born outside of Kansai.

It turned out that a whopping 91.6% use shortened, abbreviated adjectival forms, and don’t mind when others use them either. Only a few said that they don’t use them, but don’t mind when others do, and only one person claimed to using them themselves, but admittedly caring when others do. This large majority that do use these stumped adjectival forms was not influenced by location – both in and outside of Kansai they are used. As for emphasis words, it was clear that meccha (“ridiculously”) took the cake, with a leading 42.3% of participants choosing it. Interestingly enough, though to not much surprise, 36 out of the 41 who chose meccha live in Kansai – this extreme usage was something I picked up on while at university there. Regarding imported words, two words pulled ahead – misuru, coming from “miss,” meaning to fail or not achieve, came in with 42.3%, and chekkusuru, coming from “check,” meaning to check or confirm, registered at 26.8%. Somewhat surprisingly, though, it seemed that 35 of the 41 who picked misuru were from Kansai, something I had not expected. I also asked whether one uses aho or baka, mimicking the survey done in the late nineties, mentioned above. As expected, the large majority who picked aho either currently live or were born in the Kansai area, and, in contrast, a large majority of those who picked baka live or were born outside of Kansai.

Lastly, the two more open response questions. Concerning responses to the question that asked, which youth language words or phrases do you wish would go away, almost 30% of them opposed variants of using the word or “death” or “to die” in sentences, as in telling people to “go die,” or using death to express extent, as in “so hot I’m going to die,” or “this was so bad I want to die,” etc. This sentiment appeared both in and out of Kansai. Multiple responses also expressed their dislike of the over-abbreviating of words or phrases. Lastly, some responses were opposed to those who overuse certain words, saying the same word in all situations, as well as against the certain words that are overused. In regards to the question which asked participants why they think there are so many various usages of youth language, there were some quite interesting response trends. First of all, 65 of the 97 respondents chose to answer this question, higher than any other open response, non-multiple choice question. Some respondents stated that, simply, youth language allows them, in the sake of brevity, to just get their point across faster, or and do have more fun doing so, freshening up the same old same old. Similarly, some said that they want to be able to express themselves easily, and in a way that they desire. Furthermore, there was a clear trend in responses saying that they desired to communicate with their peers effectively, not needing to explain everything, yet relying on these words used within their in-groups to strengthen a sense of feeling, belonging, and camaraderie. Relating to the intense trend or consumerist driven Japanese society, a handful of respondents stated that as they’re so driven by fads, and words can be fads too, they want to try and start using new words, create their own trends, and be seen as cool or unique. In a more negative light, some said that such slang is the result of the internet or texting, especially concerning abbreviations. There was also a surprising amount of responses pointing to globalization or westernization as the cause, with people being overly sensitive to influence from outside Japan, and thereby creating language trends accordingly. Lastly, a few respondents stated that, as youth have a limited vocabulary compared to that of adults, youth need to modify the few words they know and use in order to create variety and nuance, in order to convey more complex emotions.

Sustenance for my travels!

So… what now? My senior high honors thesis project has stemmed out of this. After spending some time looking through「若者言葉に耳をすませば」(“If We Lend An Ear To Youth Language”), I realized that not only did I love the book, but now with first-hand experience under my belt, I wanted to share the knowledge in this book with even non-Japanese speakers. I therefore have decided to translate the book (it seems I shall be able to finish half of it) for my thesis, planning to finish the translation after graduation. I plan to perhaps incorporate the above-mentioned results of the survey into my thesis translation introduction, providing up-to-date examples of Japanese youth language, but, even if they don’t fit, they have provided invaluable background info to the material I’m translating, and was supremely interesting in the very least!

Also, why does this matter? Well, for those who have learned or are learning another language, and have studied abroad in that language’s native region, you may already know the answer. There is clearly a disconnect between textbook or formal learning of a language, and the on-the-ground, real-time colloquialisms, slang, etc. Furthermore, as “youth,” if one wants to try to talk to their newfound peers in their peers’ language, it will be quite the struggle if all of the youth language words go over one’s head. It is for this reason that I feel so strongly about investigating, keeping tabs on, and translating this rapidly changing information on youth language in Japan. If we are to continue to bridge gaps in this ever-globalizing world, the youth of today need to be able to communicate effectively, and comfortably, having a shared youth language to promote camaraderie.

This project has truly had an impact on me. I learned how to create a proper research proposal requesting grant money; I was given a gateway to discover my newfound interest in societal linguistics; and I was able to birth my thesis project. This project has certainly not been the end of my interactions with Japanese youth language or Japan in general – it has been a fresh beginning for opportunity! Remember, as the Japanese youth would say, it’s not さようなら (sayonara, goodbye), but rather, またね (mata ne, again yeah?).