This interview was conducted with Kyle Rhodehouse, a junior in the Alumni Memorial Scholars Program majoring in Molecular Biology and minoring in English. Kyle has been researching the developmental biology of C. elegans with Professor Van Wynsberghe.

Could you tell me a bit about your high school experience? What kinds of things were you involved in?

I was involved in a lot of science-related things- shocking, I know- and my main thing was Science Olympiads. I really loved that. I did more of the academic events, where you basically just take a test. I mostly did biology events, and honestly, I credit my ability to retain so much information to having studied the topic so many times, not just for class, but also for fun for Science Olympiads. I also did some building events, like engineering-type tasks. My school had a club that built Rube Goldberg machines for competitions. My definition of a Rube Goldberg machine would be “the most complicated and absurd way of doing a completely easy and banal task.” Doing that was really cool because I got a working knowledge of a decent number of tools and got to use my hands, but also practiced problem-solving using the scientific method, and I had a really fun time with it. We were okay at that- but we were really good at the Science Olympiads!

I was on my high school bowling team for a year, but I was in a bowling league from the time I was in second grade until my senior year of high school. That hasn’t been something I’ve been involved with at Colgate. I really wanted to go to the AMS bowling match, but I was busy that day. I hope I can go to the next one.

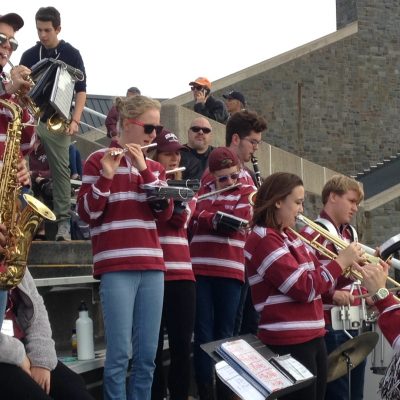

I was also in my high school’s band. I did marching band- everyone in our band did. My senior year, our band played Carnegie Hall, which was pretty cool. As an underclassmen, I was very much not a band person, I was sort of indifferent to it. It was more like “oh I’m a nerd, I have to complete the nerd stereotype and also play an instrument.” When we had out-of-class lessons, I wouldn’t go because I’d have a class like physics that I felt was more important than learning to play the trumpet. Then, senior year, it kind of hit me that, “Oh man, I’m a band person, I actually genuinely enjoy this.” I really enjoyed being in that setting of a talented, dedicated group of people. There was just something really magical about that.

I also did independent science research in high school. My school didn’t really have a very established science research program. To humble brag, I kind of pioneered that. All of my research involved insects in some way. I did two projects, one was with Red Harvester Ants, which are nasty because they bite and they hurt–I know from experience. The project had to do with their ability to sense magnetic fields, and so the container that they were in couldn’t have any metal. It was all wood and wood glue, which is not a good container for small animals. I ended up accidentally releasing around sixty harvester ants into the back of my physics classroom. Then, the year after that, I did a project with fruit flies, and they got out into my chemistry classroom. So it became this running joke that I was the “bug kid” that kept releasing insects into the school. There were three Kyles in my history class, and my teacher called me “science Kyle” to differentiate between the three of us.

I also tutored a lot my senior year, in a lot of different subjects, for middle schoolers and also fellow high schoolers. I tutored all of the sciences, algebra, geometry, trigonometry, and a lot of Spanish.

I was a Boy Scout, and I am an Eagle Scout.

Oh, cool! what was your Eagle Scout Project?

Kyle and Chemistry Professor Jason Keith at the March for Science in Washington D.C. this past April

I built these signposts- they looked like lecterns, so you had this wide base and a post that came up, and then a box on the top with plexiglass so you could read through it. I designed them for a local natural history museum in a nature preserve. They were opening up this outdoor exhibit of rescued and rehabilitated animals, so these posts sat outside and had the information like, “This is an owl- it got hit by a car, this is the kind of owl it is,” and that sort of thing. I made fifteen of those signs. It ended up being a couple thousand dollars worth of materials donated and it was over 200 hours of labor time to build them. I also worked at a Boy Scout camp for the summer between my junior and senior year of high school. I was very outdoorsy, living in the middle of nowhere for a month, in a tent. Because of that, I had a lot of friends, not just in my troop, but that worked in the council, so I was really involved in council-level things and fundraisers of that nature. I taught merit badge classes at camp and at the council office. The main things that I taught were the environmental science merit badge, the chemistry merit badge, and the geology merit badge. So, I was obviously very into science.

So is your love for nature and being in a remote setting part of the reason that you chose Colgate?

Yeah, absolutely, that is definitely a part of the reason that I picked Colgate. I was drawn to the setting and the aesthetic of it, which sounds silly, but it’s honestly so important.

How has all of this translated into your involvement at Colgate?

The main thing I do now that directly springs off of what I did in high school is Pep Band. I just finished two years of being the drum major of Pep Band, which is the person who conducts. I ran our practices twice a week and conducted at all of the games we go to, mostly hockey and football. That was something I was actually very hesitant to do. Like I said before, I originally thought that band was a very superfluous activity. And then I came here and now it’s pretty much the only thing I do. Now that I’m an upperclassmen and a little busier, I’m back to playing trumpet, but I absolutely loved being drum major and I do miss it.

I also still tutor. I tutor for the two intro biology classes. Also, for some of those classes there is something called PLTL, which stands for peer-led team learning, and I am the “team leader.” Basically, I’m overseeing a group study session, where people do activities and really engage in discussing the material in a very judgement-free setting, where people can bounce answers off of each other, and I try to guide that discussion. It’s a lot of fun.

What kinds of classes have you taken? What has been your favorite thing to study?

I’m a molecular biology major and an English minor, so at this point, those are really the only departments I am taking classes in. I feel like people think that’s a weird combo, and what I would say to that is that scientists are generally pretty bad at communicating their ideas– they’re okay at communicating them to other scientists, but they’re especially bad at communicating them to people who aren’t scientists. Especially in this day and age, I think that translation of more complex scientific ideas into everyday words that people can understand is the most important job that scientists have. I think that is the paramount issue of contemporary science in general.

I study English because, well, what is English if not the study of the most effective communicators of all time and the media in which they communicate? So my personal saint would be Rachel Carson. When Silent Spring came out, she was derided pretty heavily by other scientists saying her writing was too artsy and flowery, and prose-like, not quantitative, cold, calculating, and filled with data. Of course, we know where that went, with the impact of that book and her life. It’s that fine line between the sciences and humanities that really interests me.

There’s this field called ecocriticism, which involves nature writing, and it sort of has its roots in the transcendentalist movement of Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman. In that field, there’s this whole idea of anthropocene literature, with the anthropocene being this proposed geologic time period that we are currently in, where man has usurped the laws of nature and can alter ecosystems to suit his will, versus holocene literature, which would involve the previous geologic time period where forces of the Earth still reigned supreme, and how we communicate ideas differently across these times. I took a class on this idea, called “Fugitive Mobilities: Migration and Environmental Imagination in 20th Century America.”

I’ve definitely found that, with this being a liberal arts college where we are forced to study a wide variety of topics and subjects across departments–and “forced” is a strong word, I enjoy doing it–I have been able to cater my studies to my interests and I have taken a bunch of classes that are intersectional in that regard. Those are my favorite kinds of classes. My first year, I took a class called “History of Nature and Capital in the United States,” which talked about the history of capitalism and its intersection with how we view nature and the question of if nature is a commodity or just something to be admired and respected, and how to strike the balance between that. We read an article about the question of if a whale is technically a fish–and that has legal ramifications, because back in the 1800s whaling times, there were taxes on fish products, but if a whale is a mammal, then you don’t have to pay that tax. So of course, the fish tax people were like, “A whale is a fish, it has a tail, it lives in the water, it’s a fish!” And as it turns out, in 1818 New York, whales are ruled to legally be fish. So I think topics like that are really interesting and cool.

Could you tell me what you researched at Colgate this summer?

Kyle and his poster detailing the findings of his research. The research has since been expanded on and is pending publication, for which Kyle is the first author.

Doing research is one of the main reasons that I came to Colgate and ended up applying early decision here. My second choice was Hopkins and the reason I basically decided against that was that biology is such a huge program there. So, I got the sense that it’s very competitive and there is a lot of stress in landing a research position. I felt that if I came here, I could do research more easily.

So, last summer, I conducted research in a biology lab with Professor Van Wynsberghe. The official name of our lab is the “Nematode Molecular Biology Lab” and what we do is study a species of worm called C. elegans, which is a species of primarily hermaphroditic, non-parasitic nematode, which is the fancy taxonomic term for a roundworm. They mature in about three days, and when they’re fully grown, they’re about a millimeter long, so you can actually see them with the naked eye. In the wild, they live in soil all over the place and eat rotting material. Obviously, that’s a weird thing to study. People are like, sarcastically, “You study worms?” But they’re incredible. They were the first multicellular eukaryote, which is an organism with nuclei in its cells–so more complicated, higher organisms (we are eukaryotes), to have their entire genome sequenced, meaning that we know all the base pairs of all of their DNA. You and I are made of trillions of cells, but these worms are made of exactly 959 cells, and we know the lineage of every single one, meaning we can trace its divisions back to when the worm was just a fertilized egg. An interesting fact about C. elegans is that a canister of C. elegans survived the Columbia disaster, so they have been to space and survived intense reentry. That resilience makes them easy to study.

Kyle uses a high-powered microscope in the biology department’s microscope room to analyze phenotypic abnormalities in the worms

What we study is something called a microRNA (miRNA). miRNAs, which exist in all kinds of organisms, including human, were actually first discovered in C. elegans, and this was pretty recently, in the 90s. They’re small, noncoding RNAs, meaning that they don’t produce protein like most RNA does. Instead, they serve a regulatory function, binding to the type of RNA that does make protein, and degrading it. So it’s another way that an organism can control what genes it expresses. What I do, specifically, is study the developmental biology of C. elegans, so what controls how they grow over time. I’m basically using my microscope to look at markers for development, like how puberty is a marker for development in a person–like men start growing facial hair, but obviously worms don’t have faces, so there are other signs that I look for. I’m looking at how certain genes, including miRNAs, control that development. Molecular biology is all about figuring out about gene pathways–which genes control which other genes. I’m trying to figure out, looking at a particular gene, where that gene fits in the established pathway of the genes that control how the worms develop, grow up, and change over time. In the worms, we call that the heterochronic pathway. Humans also have miRNAs, and, weirdly enough, we have a lot of genes in common with these worms. So down the road, understanding all of this by using a simple model system like a worm can help us better understand human biology and human health.

Kyle explains the results of his research to Colgate University President Brian Casey at the Summer Research Poster Session

So what made you want to conduct research?

Well, that’s what I want to do with my life. I have always wanted to be a scientist, since I could talk. The first thing I ever took out of the library was the Bill Nye tape on dinosaurs. I would like to go to grad school, get a PhD, and continue doing biomedical research.

Are you planning on going abroad?

No, I’m not, but I am studying off-campus with the Colgate NIH study group. That’s actually one of the reasons I decided to come to Colgate, because I knew that it had this program and I knew that was something I’d always wanted to do. It’s something I’ve always been working towards, so it feels really cool to finally be preparing to go. The NIH is in Bethesda, Maryland, right outside of Washington D.C., so I will be living in D.C. and that will be really cool.

I pretty recently found out which lab I’ll be working in at the NIH. Actually, when I was first accepted, I was really determined that I would be doing HIV research, and I kind of wanted to branch out of molecular developmental biology, but when I read about this guy’s work I was just like, “This is just so cool.” I’ll be working in the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases or the NIDDK. I will be working in a lab that uses the same model organisms, C. elegans, and what they do is model rare genetic disorders using C. elegans. The types of disorders that they model are developmental craniofacial disorders. These are things that go wrong during human development, like with embryos, fetuses, all that jazz, that involve facial development. We’re talking rare diseases, things that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US–but given the high number of rare diseases, 10% of the population can have one. There are about 7000 of these so called “orphan” diseases, but we only have treatments for like 1000 of them.

C. elegans under high-powered magnification. The mature adults are around 1 millimeter long and can just barely be seen with the naked eye.

The NIH has a clinic that these people come to–people from all over the world, who have been to a bunch of doctors, and nobody can tell them what’s wrong with them. What they do is a full genome sequence and they’ll catalogue that information. Then, many years later, someone else will come in with the same thing and they’ll realize that there’s a change in one base pair, somewhere in their genome, that matches up perfectly with this other person. Then you realize, “Ok we have a syndrome, we have a disease, we know what it is, we can name it, we can start doing research and characterizing it.” So, what my lab does is it takes that data and we use CRISPR, which you might have heard of as this new buzzword that just hit the public lexicon (like “Ooooh, CRISPR!”). Basically, it’s a way of really precisely editing a sequence of DNA, so it’s a super powerful tool. Think Jurassic Park, or GATTACA, but this technology is new, so not quite so apocalyptic…yet. Anyway, we use CRISPR to try to create the same mutation the person has in the worm’s homologous gene, which is a gene that has an equivalent in another organism. The really cool thing is that we’re modeling rare craniofacial disorders, but worms don’t have faces, so what are we doing? We’re basically seeing if the mutation made using CRISPR shows some kind of weird phenotype in the worms. They have a variety of standard mutant phenotypes- they can get short and fat, we call that dumpy, they can be constipated, they can explode out of their vulvas. So, if something is wrong with the worms, then people can start doing drug trials, and seeing if it will alleviate that phenotype in the worm, and then maybe it could alleviate the symptoms in the people.

C. elegans as seen through a microscope. They leave squiggly trails as they eat their way through the E. coli on the petri dish.

And obviously, even though we’re talking about a rare disease that doesn’t affect that many people, to those few people it does affect, it means the world. And that is work that I am really excited to do. I’ve always thought that the purpose of science is to get a better understanding of the universe and our place in it, but the reason that I’m so attracted to it is that I see it as this agent of change, of good, and of helping people. That’s sort of why I don’t want to necessarily be a medical doctor, which is obviously a really rewarding job. But, I feel like practicing medicine, in the traditional sense, is helping a few people on a very personal level. But, to me, research is a way of doing that on a mass scale, making discoveries that can affect people for many people for many years to come.

How are you planning to use your AMS funding?

It is possible to use your AMS funding for the NIH summer program. If, for whatever reason, someone doesn’t have space in their lab or they’ve already hired some other person, then you could apply to use Colgate funding, such as the AMS grant. My position is subsidized because the director of the lab took me early enough that I could get that. He has actually never worked with a Colgate student before. We have a list of labs that we consistently go to and that take Colgate students frequently, and Colgate students go back for post-bacs and work in those labs. But, this is a new person, who has not done this before, who needed to learn about the program before he took me. But, obviously, I think was hired because of my experience at Colgate working with the same organism, which gave me the desired skill set to be able to do this research. And I got into that lab, so I can use my AMS money for something else.

I am currently planning, so I’m still in the early stages, and who knows, things could fall though–I once planned a different project that ended up falling through. But, currently, my goal is to go to Madagascar and volunteer at an NGO that does some charity work with wildlife, specifically lemurs. Lemurs only live on Madagascar and some of the surrounding smaller islands. I think it’s a cool idea to use the AMS funding for a volunteering purpose. Obviously, I think it’s an absolutely wonderful opportunity to be given this large sum of money to use however I want. And when I started looking into Madagascar, I realized this was a less developed country that doesn’t have a lot of infrastructure, has had a lot of political turmoil, and so on. So, I think being able to spend my grant money to help out there, do some charity work, is a really cool idea.

The organization I’m currently looking into rescues and rehabilitates ring-tailed lemurs that were captured for the pet trade or for bush meat. I would be helping care for them, and doing some work on recently released animals, tracking them and learning about their ecology. I would also like to do some travelling to some of the various national parks in Madagascar. I want to be able to see the wildlife, the biodiversity of this unique place. The cool thing about AMS is that you don’t have to use your funding on exactly the thing that you’re studying. I am in molecular biology–I’m looking at the stuff that makes cells go. This is broad, organismal biology. It’s getting me to explore this other side of my interests. I love zoos, I love animals and always have. I grew up on Zoboomafoo. I did a project on Madagascar in sixth grade. That’s the other cool part about AMS, that you can take something that you find interesting and turn it into an actual, real-life experience.

What are some of your favorite things about Colgate? What do you think could improve?

The thing that I like about Colgate is that it is truly a community of intellectuals, in the fullest sense. That’s one of those things that I don’t think I realize until I leave campus. There’s something nice about being able to have an intelligent conversation with someone about Nietzsche or whoever. I like that. I think it’s a really valuable thing to have students that are informed, deeply care about the world, and can have an intelligent debate or discussion about a topic. I think that happens a lot here and I really, really appreciate it. People take their class learning and apply it to life outside, then they take their life and apply it to class. I see that often.

Another reason I came here is the small class size. I think it’s really interesting, when I talk to people I know who go to a much bigger school, they say that I seem to have more work than they–I actually have to do all of my readings. Because when you’re in a giant lecture class with 700 people, it doesn’t matter if you did the reading. But, here, you’d better know what you’re talking about because you’re in a class with fifteen people. The biggest classes I’ve had were my intro bio classes, which were about 80 people, which is still a lot smaller than a lot of the giant classes at other places. By extension of the small class size, I have professors that I would consider my friends. I absolutely adore the professors here–people whose office hours I can go to and just spitball about my life, or elaborate on a point that I thought was interesting in class and really hone in on my interests. The professors here are so responsive to that. They work at a small, liberal arts college because they want that just as much as you do. And they’re obviously incredibly brilliant. It’s great to go in and talk to somebody who just oozes knowledge, who is just casually brilliant–that’s really wonderful.

I think my number one issue with Colgate, that stems into a lot of aspects of campus life, is the lack of economic diversity. I get it–I understand why this, as an institution, as a product of its history, is the way it is, but I think we can improve. The New York Times did a report on economic diversity and student outcomes at Colgate, and it says that Colgate students have the second highest median family incomes of the elite colleges in the U.S. And in another New York Times article that came out last year, Colgate is number seven on the list of percentage of students from the top 1% versus the bottom 60%. Colgate is very proud of the high earnings of its graduates, people landing lucrative professions and amazing jobs–and that’s great–good for them. But, you look at these stats and realize that it’s not people coming into Colgate from the bottom income bracket that become the high earners that Colgate is so proud of. It’s people who already come from that background. And maybe that’s not so much a Colgate problem as it is an elite college problem and a United States as a whole problem. But, that issue definitely manifests on campus. Beyond that though, I think income is a bad way of judging student success, I really do–there’s so much more to life. I do think we’ve made some good strides though, like they aren’t asking for official test score reports anymore, so you don’t have to pay to have your SAT/ACT reports sent to Colgate before you’re accepted. It’s small, but it helps. We’re currently not need-blind, which makes me annoyed, especially since that makes the idea of meeting 100% of demonstrated aid moot, but I know we’re taking steps in the right direction.

In very implicit ways, I think that this lack of economic diversity leads to a homogenous student body. I think we like to pride ourselves on diversity, but we know the ways that economic diversity relates to racial diversity, and I think you can see that here. By extension, I think we have a very exclusive social scene, which has its own problems. Because we have the delayed rush system, statistics about the percentage of students in Greek life can be deflated by counting all first years as non-greek, but they aren’t eligible in the first place. That being said, if you go by the statistic of Greek Life as a ratio of the student body, it is a minority. But, it is a vocal minority. It’s a force, it’s a presence, it’s the dominant social scene. By its nature, Greek life is exclusive. I think that’s an issue.

I also think that we have a problem with stress culture. I think the student body prides itself on the philosophy of “Work hard, play hard,” and that works–to a point. But you’re going to crash and burn at some point. I think that because of that mantra, there is a pressure to constantly go out and there is a pressure to constantly achieve. That’s the downside of being a part of community of intellectuals. It’s not competitive in the sense that you’re trying to be better than other people, but it’s a social expectation to be like other people. With that, this is a hard school, there’s no sugar coating it. Is this a high-caliber, elite school that prides itself on the difficulty and rigor of its academic curriculum? Absolutely. Is it harder than other schools of the same caliber? Probably not. Do I enjoy academic rigor, and is that a reason I came here? Absolutely! It’s just useful to keep in mind that there are consequences to that.

Also, not many people go to sporting events–I think we can lack school spirit–Colgate just isn’t the kind of place that is particularly enthused by sports. People don’t go to things that they’re not directly involved in, and I think there could be a thousand reasons as to why, but I think a big part of it is the drinking culture. It’s college, people drink, obviously. But, I think there’s often this idea that if there isn’t going to be alcohol there, well, people aren’t going. Of course, that’s a self-fulfilling prophecy, because now I won’t go to that party because I don’t think anyone else will be there. People don’t go to the dry events, even on Spring Party Weekend. It’s a little weird, a little disappointing, and I definitely think that’s unique to Colgate.

That being said, I will definitely look back on my time here with fondness. I guess I’m so critical because I care about this place so much. I have really, truly enjoyed my Colgate career so far, and I’m so excited to see what senior year brings!