Over winter break, I traveled to Europe to study theatre, with a special focus on the work of William Shakespeare. This project gave me the chance to witness the Bard’s work through its intended medium (live performance),

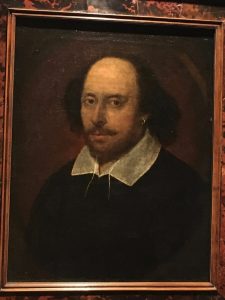

Painting of Shakespeare found at the National Portrait Gallery during some downtime

which radically expanded my understanding of staging, interpretation, and the importance of theatre. Here are a few highlights.

My first experience in London was a workshop of Sweat, a contemporary play by Lynn Nottage that focuses on working-class communities in Reading, a small, struggling city in Pennsylvania. I happen to be from Reading, so I was eager to discover how my hometown was portrayed through theatre. Over the two-hour workshop, we focused on a specific scene of the play and completed exercises in reading and interpretation. In my favorite exercise, we played the scene with a partner. With each line, we had to take a step either forward or back: forward if our line was trying to connect with the other person and back if we were trying to disconnect. Some lines were ambiguous as to whether they were positive or negative, so my partner and I practiced reading them different ways. I learned that, even when the text is kept exactly the same, the lines can be read in vastly different ways, depending on the players’ conceptions of the characters’ backgrounds and motivations. This was a powerful lesson that I kept in mind throughout my trip.

The view of the tiered balcony at the Barbican’s production of Macbeth. To the left is the stage, which was covered by a copper-colored metal curtain to hide the unique stage setup before the play began.

The first play that I saw was the Royal Shakespeare Company’s production of Macbeth, which was staged at the Barbican Theatre. I was fascinated by what the production did with King Duncan (who is killed by Macbeth). I had always read Duncan as a noble and worthy king, but this production portrayed him as old and incompetent. His lines were kept in exact accordance with the text, but the way he delivered them (as well as his gestures, costume, and staging) changed my impression of him. The play was full of interpretive choices like this; for example, in the moment before Duncan names Malcolm as his successor, everyone on stage looks at Macbeth, expecting him to be chosen. When Duncan chooses Malcolm, everyone is shocked, and the audience gets the impression that Macbeth has been treated unfairly.

Stage design at the Barbican

I also attended a production of Romeo and Juliet, which, like Macbeth, was performed at the Barbican. The staging was very simple, with this box serving as the centerpiece for the entirety of the play. Actors would sometimes climb on top of it, including during the famous balcony scene.

After that was Doctor Faustus, which was playing at the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse and was written by Christopher Marlowe, a contemporary of Shakespeare’s. The coolest thing about the production was the playhouse itself. Although the playhouse is very new, it was built using plans from the 17th century, which means that there is no electrical lighting within the theatre—everything is candlelit. Actors drew attention to themselves by carrying their own candles, and chandeliers hung from the ceiling. The stage was small, with three doors in the back for entrances and exits. There were no entrances on the wings of the stage, but some players actually entered through the audience seating, literally climbing over people and barriers to get on stage. (This was usually humorous.) Although Faustus gets dragged to Hell at the end of the play, it’s not all serious. Much of the middle of the play is actually hilarious, as the players play tricks on each other and even the audience members themselves. The audience was right next to the stage, so sometimes the players would flirt with or insult them! In this way, Faustus showed me how humor (which doesn’t always translate well in written text) comes to life on stage.

The Sam Wanamaker Playhouse is set up here for a performance of Macbeth. Note the proximity of the audience to the stage, both on the wings of the stage and in the front. The chandeliers hold real candles and can be raised and lowered at will.

Finally, I returned to the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse to see a different production of Macbeth, as I was eager to compare it to the one I had seen earlier. This production was more period-appropriate, with older-looking costumes, music, and props. This production, in comparison to the first one, portrayed Duncan as a virtuous king, which made it a bit more difficult to justify Macbeth’s decision to kill him. The production also reused most players in multiple roles, whereas the RSC production had a bigger company and did not duplicate as many roles. One player, for example, portrayed Duncan, a witch, a murderer, and a courtier. This was a very common practice in Shakespeare’s time because, by reducing the number of actors, the company saved money on wages.

In all, the trip was far more rewarding than I ever could have imagined. I have a better understanding of the multiplicity of interpretations that can be derived from a single text, which should be very helpful as I write my honors thesis this spring. I’ve also come to understand the immense importance of live theatre—not just to Shakespeare nerds like myself, but to everyone. I doubt that all my fellow theatregoers were English majors, but everyone was laughing together in the funny moments and holding their breaths in the tense ones. Furthermore, since tickets were going for as little as £10, the productions were accessible to people from a variety of socioeconomic backgrounds and stages of life.

One of my favorite moments was when I was leaving a theatre at the end of a production and overheard young children discussing the play. I expected them to only be interested in the fight scenes, but it turned out that they were actually engaging in an impressive level of analysis—not only had they followed the action of the play, they understood it well enough to comment on the way in which it was done! It turns out that, in the U.K., theatre really can bring diverse people together. In the U.S., however, theatre is often less accessible, as quality theatre can be quite expensive. That’s why it’s so important that people support local productions when they can and that the government provide financial support through programs such as the National Endowment for the Arts. The theatre is magical, educational, and one of the best untapped cultural resources for bridging barriers between people. It matters. And I’m incredibly grateful for the opportunity to experience it for myself.