Victoria Street, the inspiration for Diagon Alley in Harry Potter

Over Spring Break, I travelled to Edinburgh because in 2004 it was named the world’s first UNESCO City of Literature. This means that Edinburgh essentially pledged to make a commitment to promoting the past, present, and future of literature. As an aspiring creative writer, taking Advanced Fiction Writing Workshop this semester at Colgate, I was particularly interested in how Edinburgh’s palpable literary culture fosters literary creation. Thus, I frequented literary spaces that were either well-advertised or that I discovered through my own exploration, and engaged in some experimental writing of my own in many of those spaces.

Before the trip, I read Crowded With Genius: The Scottish Enlightenment: Edinburgh’s Moment of the Mind, to parse out the history of literary culture in Scotland. There were many authors and projects discussed in the book, and I was inspired by one of the examples to do my experimental writing as a tale of a quest. Having read about the many famous writers to hail from Edinburgh, I imagined that there must be some secret to literary success hidden in among its streets. My quest was to discover the (totally cliché!) literary grail. In other words, I was aiming to discover how Edinburgh could help me take my writing to the next level. My quest began in The Elephant House.

Thomas Riddell’s grave in Greyfriar’s Kirkyard, the inspiration for Tom Marvelo Riddle aka Lord Voldemort in Harry Potter.

Upon my arrival, travel backpack in tow, sleepless, and needing to escape the rain, I went to The Elephant House. This is the incredibly touristy, “birthplace of Harry Potter,” where J.K. Rowling wrote sections of the series. Her table is located in the back, with a view out the window of Greyfriar’s Kirkyard and the Edinburgh Castle, which allegedly inspired character names and Hogwarts, respectively. I had a lovely view of the cash register, but I endeavored to write all the same. After, I went to Greyfriar’s Kirkyard and found the grave of Thomas Riddell, the inspiration for Tom Riddle, aka Lord Voldemort. I also walked on Victoria Street, the alleged inspiration for Diagon Alley.

A plaque commemorating the early writing of Harry Potter, approved by J.K Rowling and outside the former Nicolson’s cafe—now Spoon cafe.

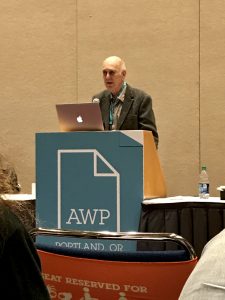

Then, I went on The Edinburgh Book Lovers Tour. Hosted by a local author, this tour took us beyond the touristy Royal Mile and to significant literary sites that I wouldn’t have known were literary sites otherwise. For example, we went to the medical school where the doctor who inspired Sherlock Holmes worked, and to a café that is genuinely the one where J.K. Rowling wrote the first chapters of Harry Potter, as affirmed by J.K. Rowling herself. It used to be called Nicolson’s, and is now called Spoon, and there is no acknowledgement of Harry Potter inside the café at all.

That night, I went on a literary pub tour, which was essentially a walking theatrical production of two men debating whether the literary history of Edinburgh was one of debauchery or one of esteemed academia. The ultimate conclusion was that it was a mix of both. However, my main takeaway, in line with the tour I had taken earlier, was that any space could become a literary space, and that Edinburgh abounded with them.

Looking up at the Walter Scott Monument, the largest monument to a writer in the world.

The next day, my intended literary destinations were the Walter Scott Monument, the Scottish Storytelling Centre, the Scottish Poetry Library, the Museum of Edinburgh, and the Burns Monument. The Walter Scott Monument is the tallest monument to a writer in the world, and I was disappointed that it was closed to visitors so I couldn’t go to the top. The Scottish Storytelling Centre was a quiet place but it had ample space to write and had I been on a different week there may have been storytelling-related programming. The poetry library was very similar. Both of those two places were fairly modern, and explicit about literary creation. I found myself more intrigued by the places that were more historical and that had an opaqueness to their literary connections. The Museum of Edinburgh was an eclectic house of Scottish trinkets, and the whole museum was framed as a narrative of Scotland. Additionally, each object had a label that told its story, and I was again enthralled by the degree to which ordinary objects could take on literary heritage for the sake of how they were used, or even how they were seen.

That night, as I climbed Calton Hill by the Burns Monument, I turned to look at Arthur’s Seat, evidence of Edinburgh as a volcanic landscape. There, taking in the view, I decided that I’d found my literary grail. From what I’d seen and learned about Edinburgh’s literary culture, I understood what made its writers successful, how Edinburgh’s approach to commemorating those writers matched that ethos, and how Edinburgh could provide fodder for future writers.

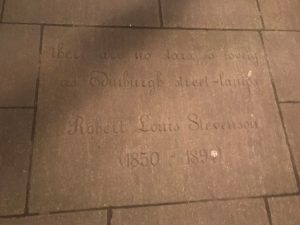

Edinburgh street lights…

Edinburgh’s writers wrote about Edinburgh, but they wrote about it in the unique way that they saw it. They wrote about Edinburgh’s buildings, gravestones, alleyways, winding streets, walls, and streetlights, but they imagined them as more—as magical schools, complex characters, and passageways to other worlds. Then, through vivid descriptions, they effectively conveyed the unique way they saw those things to the rest of the world. Edinburgh’s writers were exceptionally creative in their visions, but everyone sees the world in their own unique way, and anyone can craft a story based on their own vision.

Since literary culture in Edinburgh is largely unlabeled, or at least not overtly advertised, the way I necessarily explored Edinburgh allowed me to practice the skill of intentionally and uniquely seeing. As I did my own writing, I focused in on describing the way I saw Edinburgh as I ran and walked many miles through its streets and closes. And finally, this all reinforced something I’d learned in my Fiction class, which is that your descriptions don’t just describe the story’s world, they describe the way your character sees the world.

…and Robert Louis Stevenson’s famous quote about them!

I rounded out my explorations of Edinburgh by writing in Spoon Café, reflecting during tea in the Signet Library, listening to live Scottish music in the Sandy Bells pub, and studying in The Writers Museum. Overall, I found no shortage of literary locations, and I had fun finding them, particularly those off the beaten path. I also found my journey to be a more genuine and rewarding way to travel as I oriented my days around a goal that was tied to my passion for writing as opposed to sticking to more classic itineraries for Scottish tourism. I also came to identify myself as a writer, and am both inspired and equipped for future writing endeavors.