Alumni Memorial Scholar Sydney Loria ’18 used her AMS Grant to travel to Italy during the summer of 2016. For two weeks, Sydney lived in Verona, where she volunteered for the Juliet Club. Her goal was to understand how Shakespeare’s character Juliet Capulet remains relevant in modern society–and why so many people from around the world write letters to a fictional person. The following post describes her experience and results.

The story of Romeo and Juliet has inspired people for years, teaching us that love at first sight is real and true love exists. It is a narrative that is understood across generations and cultures as the archetypal story of love in its purest and deepest form. It introduces us to a character that is both childish and mature, naïve and wise, careless and cautious. For years, people have been turning to Juliet Capulet for advice about love and life as if she knew all the answers as a thirteen-year-old girl. In our Western culture, we see such young love as puerile and yet still place so much faith in the young lover. It is this seemingly hypocritical attitude that inspired me to travel to Verona, Italy and volunteer for the Juliet Club.

The tradition of leaving letters for Juliet has been around for centuries, but the club was officially founded in the 1990’s with the purpose of giving answers to lost souls. I was first introduced to the organization after watching Letters to Juliet, the popular film that came out in 2010. I found hope and inspiration in the idea of the Juliet Club, and I arranged to spend two weeks in Verona working for the club and answering some of my own questions about Juliet and the pivotal role that she continues to play throughout history.

One of the most famous tourist attractions in Verona is Juliet’s Balcony. Home to the famous bronze statue with the lucky breast and the wall where thousands of notes are posted each year, it is where people travel when they seek the advice of Juliet. The plethora of languages spoken in this small area made me more aware of the fact that Juliet’s love is such a global phenomenon. People from all over the world, with incredible differences, come to Verona with the common goal of seeking the advice of the star-crossed lover. The letters are placed inside a red mailbox, and one of the duties of the Secretaries of  Juliet is to empty the mailbox and bring the letters to our office. Juliet’s Balcony is a symbol of her love for Romeo, and when standing there, one can imagine the famous balcony scene that takes place in Shakespeare’s play. Being in a place filled with the promise of such love makes us forget rationality and allows us to believe in true love and the ultimate sacrifices that people make to maintain it.

Juliet is to empty the mailbox and bring the letters to our office. Juliet’s Balcony is a symbol of her love for Romeo, and when standing there, one can imagine the famous balcony scene that takes place in Shakespeare’s play. Being in a place filled with the promise of such love makes us forget rationality and allows us to believe in true love and the ultimate sacrifices that people make to maintain it.

The Secretaries of Juliet take on the role of Juliet, and answer each letter that is sent to Verona. After watching the movie that the Juliet Club inspired, I had expected to find a table of experienced woman answering the pleas of these heartsick women. However, I found a table of high school girls. I learned from them that as part of their schooling, they were required to volunteer over the summer at a place that matched with their schooling specialties. As these girls had all chosen to attend high schools with language-intensive programs, they chose the Juliet Club to practice the variety of languages that they were learning. I was left wondering how a group of such young girls, including myself, held the wisdom and ability to truly help the  hundreds of people with problems that many of us had not yet even faced ourselves.

hundreds of people with problems that many of us had not yet even faced ourselves.

Throughout my time volunteering, I found that the letters generally fell into a couple of categories. The most prominent of which were letters from those who faced a crossroads in their love lives. There were also letters that were written for the sole purpose of expressing personal content in a relationship. Many letters addressed problems that were not at all love related, and the type that I least expected came from school children. Many teachers instructed their students to write to Juliet as an exercise after reading the play; these letters proved to be the most amusing. Many of the students reflected on specific details from the play and asked Juliet about how she could be so foolish to think that she had found true love at such a young age. Other students wrote to Juliet as a means of practicing their English skills. The  students showed a genuine curiosity about the story of Romeo and Juliet, and they were faced with the same questions that I had wondered about before leaving for Italy. The exposure to Romeo and Juliet at such a young age, and across many countries, demonstrates how literature plays an important role in spreading the notion of Juliet’s wisdom and ability to help others who are facing difficulties.

students showed a genuine curiosity about the story of Romeo and Juliet, and they were faced with the same questions that I had wondered about before leaving for Italy. The exposure to Romeo and Juliet at such a young age, and across many countries, demonstrates how literature plays an important role in spreading the notion of Juliet’s wisdom and ability to help others who are facing difficulties.

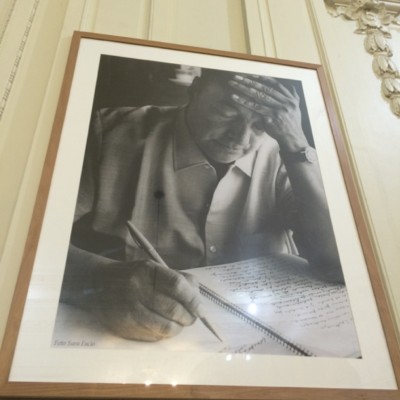

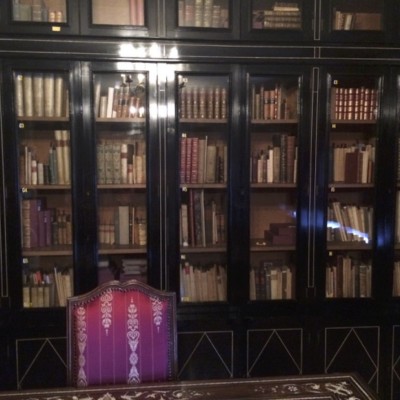

The history of the Juliet Club became quite apparent when one day I was able to visit the archives. This room housed letters that had been received each year since the foundation of the club. The man that took us to the archives also explained that they were currently working on a project where the entire manuscript of Romeo and Juliet was being copied, each line by a  different person. These traditions and history succeed in bringing people together and surmounting the vast differences that are seen between cultures and beliefs. I learned that the Juliet Club is a very welcoming and open organization, allowing anyone that walks into the office to ask questions and even offer their own advice by means of answering a letter. We can’t offer each person that writes to us the perfect advice or provide them with all the answers, but we can give them love and hope. The ability of the Secretaries, even though we were all young, to successfully respond to the variety of letters we received was dependent upon our ability to provide a sense of hope. Hope is what has brought millions of people over the years to Verona and to Juliet’s Balcony. The ability of Juliet to find a love that she was willing to die for is inspiring, and although the outcome of her story can be described as nothing short of

different person. These traditions and history succeed in bringing people together and surmounting the vast differences that are seen between cultures and beliefs. I learned that the Juliet Club is a very welcoming and open organization, allowing anyone that walks into the office to ask questions and even offer their own advice by means of answering a letter. We can’t offer each person that writes to us the perfect advice or provide them with all the answers, but we can give them love and hope. The ability of the Secretaries, even though we were all young, to successfully respond to the variety of letters we received was dependent upon our ability to provide a sense of hope. Hope is what has brought millions of people over the years to Verona and to Juliet’s Balcony. The ability of Juliet to find a love that she was willing to die for is inspiring, and although the outcome of her story can be described as nothing short of tragic, she was strong and she was determined and she was hopeful that one day she would be reunited with her Romeo. We all strive to attain the ultimate goal of love and success, and the key to finding these things is finding hope and strength. Juliet’s story embodies such feelings and the ability of the Secretaries to translate these messages into our letters is what makes the Juliet Club successful and encourages the people of the world to continue to put their faith in Juliet.

tragic, she was strong and she was determined and she was hopeful that one day she would be reunited with her Romeo. We all strive to attain the ultimate goal of love and success, and the key to finding these things is finding hope and strength. Juliet’s story embodies such feelings and the ability of the Secretaries to translate these messages into our letters is what makes the Juliet Club successful and encourages the people of the world to continue to put their faith in Juliet.

All the Secretaries that I worked with had the same feelings regarding love and the meaning behind the character of Juliet. We still keep in touch, and in general, this was a very powerful and eye-opening experience for me. I loved being able to feel a connection with people from all around the world, and I really appreaciated the welcoming environment of the Juliet Club. The people who write to Juliet don’t expect to receive all the answers to their problems in our responses. They want the courage and strength to be able to decide what is best for them, and if we can offer a little personal advice along the way, then they can feel like someone is listening. I loved the time that I spent in Verona, and I am positive that Juliet will continue to remain a symbol of love and hope for generations to come.

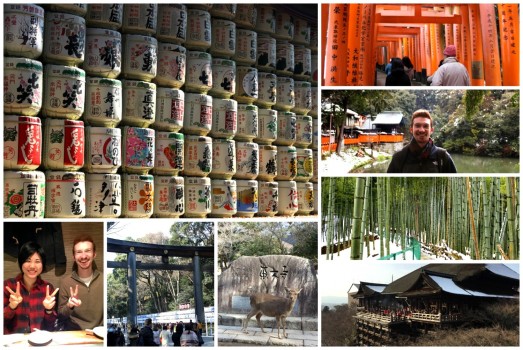

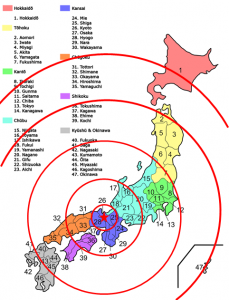

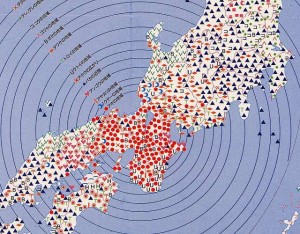

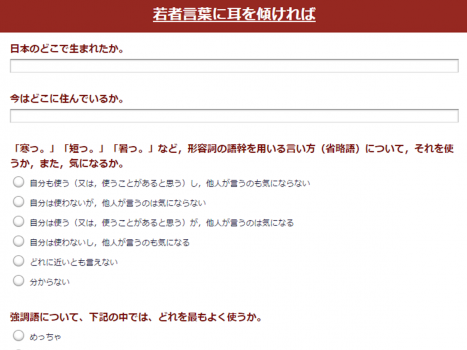

As for the survey itself, I created one version that could be distributed in person, via paper, and online as well. I created some unique questions of my own, based some off of topics in the youth language book mentioned before, and mimicked some asked in the Japan Agency for Cultural Affairs national polls, to allow for the possibility of seeing a difference in results over time. The question types ranged from multiple choice (“Which of the following emphasis words do you use most often?”), to fill-ins (“If you had to pick a youth word you wish would go away/out of fashion, what would it be?”), to short answer (“Why do you think there is such variety in current youth language usage patterns?”), etc. I also asked birth location and current residential location in order to guarantee an accurate knowledge of participant geographical influence.

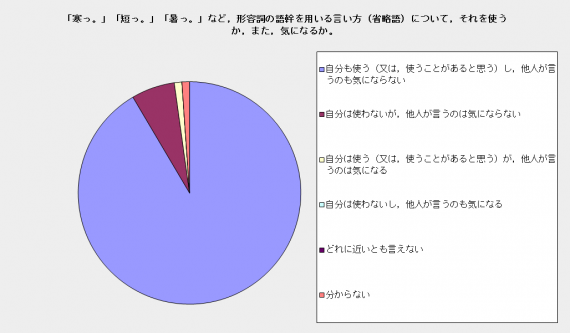

As for the survey itself, I created one version that could be distributed in person, via paper, and online as well. I created some unique questions of my own, based some off of topics in the youth language book mentioned before, and mimicked some asked in the Japan Agency for Cultural Affairs national polls, to allow for the possibility of seeing a difference in results over time. The question types ranged from multiple choice (“Which of the following emphasis words do you use most often?”), to fill-ins (“If you had to pick a youth word you wish would go away/out of fashion, what would it be?”), to short answer (“Why do you think there is such variety in current youth language usage patterns?”), etc. I also asked birth location and current residential location in order to guarantee an accurate knowledge of participant geographical influence. It turned out that a whopping 91.6% use shortened, abbreviated adjectival forms, and don’t mind when others use them either. Only a few said that they don’t use them, but don’t mind when others do, and only one person claimed to using them themselves, but admittedly caring when others do. This large majority that do use these stumped adjectival forms was not influenced by location – both in and outside of Kansai they are used. As for emphasis words, it was clear that meccha (“ridiculously”) took the cake, with a leading 42.3% of participants choosing it. Interestingly enough, though to not much surprise, 36 out of the 41 who chose meccha live in Kansai – this extreme usage was something I picked up on while at university there. Regarding imported words, two words pulled ahead – misuru, coming from “miss,” meaning to fail or not achieve, came in with 42.3%, and chekkusuru, coming from “check,” meaning to check or confirm, registered at 26.8%. Somewhat surprisingly, though, it seemed that 35 of the 41 who picked misuru were from Kansai, something I had not expected. I also asked whether one uses aho or baka, mimicking the survey done in the late nineties, mentioned above. As expected, the large majority who picked aho either currently live or were born in the Kansai area, and, in contrast, a large majority of those who picked baka live or were born outside of Kansai.

It turned out that a whopping 91.6% use shortened, abbreviated adjectival forms, and don’t mind when others use them either. Only a few said that they don’t use them, but don’t mind when others do, and only one person claimed to using them themselves, but admittedly caring when others do. This large majority that do use these stumped adjectival forms was not influenced by location – both in and outside of Kansai they are used. As for emphasis words, it was clear that meccha (“ridiculously”) took the cake, with a leading 42.3% of participants choosing it. Interestingly enough, though to not much surprise, 36 out of the 41 who chose meccha live in Kansai – this extreme usage was something I picked up on while at university there. Regarding imported words, two words pulled ahead – misuru, coming from “miss,” meaning to fail or not achieve, came in with 42.3%, and chekkusuru, coming from “check,” meaning to check or confirm, registered at 26.8%. Somewhat surprisingly, though, it seemed that 35 of the 41 who picked misuru were from Kansai, something I had not expected. I also asked whether one uses aho or baka, mimicking the survey done in the late nineties, mentioned above. As expected, the large majority who picked aho either currently live or were born in the Kansai area, and, in contrast, a large majority of those who picked baka live or were born outside of Kansai.