Week 4: Memorials

The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe is a chilling reminder of the Holocaust . Located in the center of Berlin its towering stone slabs and narrow pathways work to make you feel isolated and disoriented. It’s a reminder of the horrors that have taken place in Germany. It is also a way to never forget.Memory has a way of acting on a community. It makes people feel connected with those in the past or pride in where they’ve come from. We are made to never forget our triumphs, downfalls, or losses. Whatever their purpose memorials and monuments are created to convey a certain collective feeling and memory. Have the monuments you’ve seen since you have been away been chilling and somber or have they conveyed a sense of triumph in your country. Maybe they’ve conveyed a calm sorrow as as the Belgian countryside does, dotted with cemeteries full of soldiers lost in World War I. Each country is unique in how they represent their past. Tell us about the memorials you have seen. How did they make you feel? How did those who came to visit act while they were there. Was remembrance of an event limited to monument or could you feel it reverberating throughout the community, even years after it occurred?

Oneida Shushe

I left my room on a cold, windy Sunday morning to take a picture of the Reformation Wall in the Parc des Bastions for this blog. The wall features four tall men carved into a wall. One of them is John Calvin, the leader of the Protestant Reformation movement in the 16th century. Calvin continued what Martin Luther started with the Reformation. He ruled over Geneva and punished people if their religious beliefs did not match his. I didn’t know that this historical event happened in the very city in which I’m studying, so I’m glad the monument taught me this.

Even though it was still icy-cold, I looked around the park a little bit more. I saw busts of men in suits raised off the ground in columns. Then I remembered that there are busts of men in the same style just inside the University of Geneva next door. There are so many important people Geneva wants to remember—these guys basically had their own mini monuments—and they are all men. There is a statue of a woman in its own section of the park a few steps away: she is sitting on a slab naked. These statues represent the historical and ever-present inequality between men and women. Thankfully, this problem is receiving more and more attention—including at my internship at the World Health Organization, where the Director-General is calling for more representation of women in the organization. Maybe over the years, monuments in Geneva and across the world won’t be just men in suits, religious clothing, and battle gear. Maybe in the future, a young female student will leave Parc des Bastions inspired by statues of other women who came before her, so that enduring the numbing cold on a Sunday morning would be worth it.

Micah Dirkers

When you think about the role that memorials play in honoring history, tradition, or the fallen, you often think of a formally dedicated space or structure that commemorates the aforementioned; yet does a memorial or monument always have to be formally dedicated as such in order to achieve its aim? My answer would be yes and no; here is what I mean:

Yes, in the sense that there does need to be some physical landmark, monument, or memorial that is built, designed, and advertised to be remembered in a historically significant way. This memorial functions as the embodiment of a story, of information, and of people—who was there, what happened, why did it happen. As far as I saw in Scotland, there were very few formal memorials that dedicated a particular space to recount a downfall or triumph; yet there were a few that I did see (and I speculate that there were many more that I did not see). Indeed, they were “memorialified” by surrounding information signs, placards, boundaries of reverence, and tour guides who had learned the history and who would pass it on to spectators. There was always a sense of reverence and mystery about these memorials, as one could not step on or touch certain areas of the memorial. One notable example was Alnwick Castle, famously known for its use as the castle featured in the first two Harry Potter movies. There were information signs and pamphlets detailing the history of the space, as chiefly a residence for a noble family, but the castle also functioned as a stronghold during the War of the Roses. Spectators were forbidden from gaining access to the family’s private spaces, and instead, they were allocated to publicly commemorated spaces. In such commemorated spaces, it seemed as if the spectator is meant to feel some connection to the past, facilitated by the posted information and tour guides, as if they were trying to convey the event that occurred in the past to have effect on the viewer today. Perhaps that experience is easier for citizens of Scotland to have, but as an exchange student, I can say that I did not feel deeply connected to the few formal memorials I witnessed abroad.

Complimenting what I wrote above, I would also respond no, in the sense that there are many nontraditional memorials other than specifically dedicated spaces that you would not think of as memorials. To elaborate, for example, around many locations in Scotland and in Edinburgh, there were “memorials” in the forms of regular churches, contemporary houses, Highland hills, Scottish fields, statues, parts of a city street, and more, but you would not have known that they were memorials just by looking at them. These were the majority of the memorials that I witness abroad, and interestingly, I felt more connected to these memorials than the formal ones, perhaps because I had to use to use my imagination to “memorialify” them for my own experience. I only knew of their historical significance through stories passed on by people (though in a colloquial way, not from a tour guide). For instance, during my homestay with a Scottish family, their small country house which appeared perfectly normal on the exterior was the location where the plan to defame and execute Sir Thomas More was hatched (although there were other locations too). For my experience, that information did not fundamentally change the way that I experienced the homestay; yet without the typical, external information telling me what to remember, I found myself imagining what the space must have been like at the time: what did the conspirators say, what did they have for dinner, was anyone else aware of the meeting, how did the plan hatch, and more. While it was interesting the imagine this, it did not creep me out or negatively impact my stay with the family, but it did remind me of the potential for a “normal” space to function as a memorial, even if not formally commemorated.

In this way, the city of Edinburgh, the nation of Scotland, and everything during my experience abroad were a type of “memorial” which represented a culmination of historical happenings into what we know call the present. While I can not say that the few formal memorials I witnessed impacted me abroad, it was engaging to imagine how many of the not-so-formal memorials conveyed a historical message, without being specifically designated as memorial. Thus, I can say, undoubtedly, that the experience of going abroad is a “memorial” which will reverberate throughout my life as a positive experience even years after it occurred.

Jenny Lundt

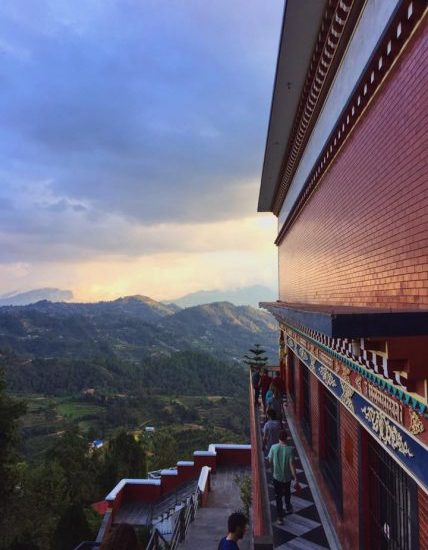

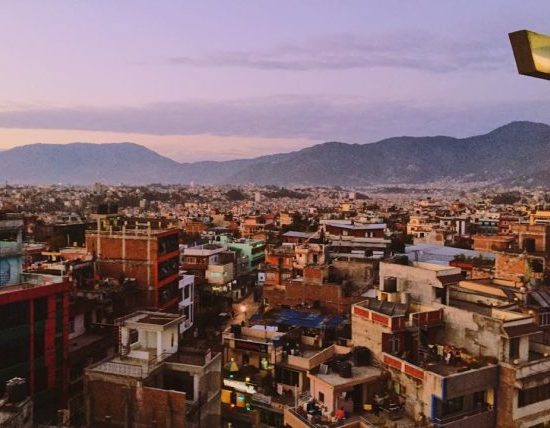

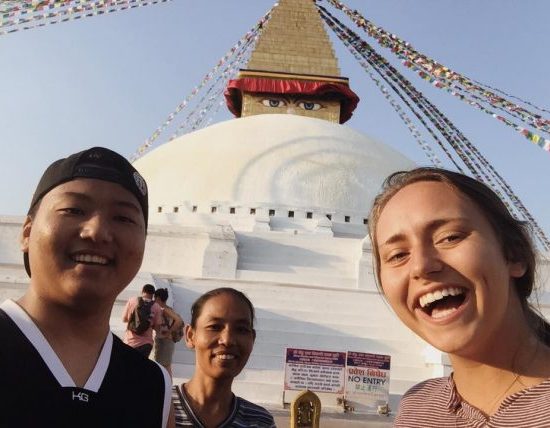

Monuments in Nepal are not as how you would think about them in Europe or the US with neat cemeteries lining the countryside or giant metal statues of past rulers. Throughout my journeys in Nepal, I found that the way people pay homage to the past are through temples, monasteries, shrines, tombs, and places of worship. One of our excursions with the program was to Namo Buddha monastery, about 2 hours outside Kathmandu. The monastery sits on top of an elevated hill which provides sweeping panoramic views of the hills in all directions. Though it has captivating views, it is much more than simply a beautiful place. This place is one of the holiest places of Buddhist worship in the world.

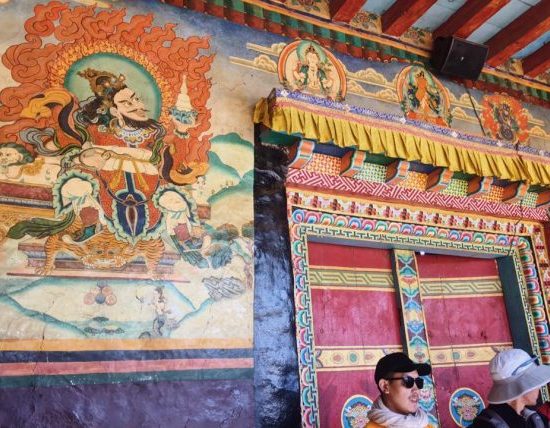

According to the creation story, thousands of years ago, a prince stumbled across a tigress and her 5 cubs on the verge of starvation on the fringes of the jungle. Noticing how her cubs were dependent on her for life in the form of the non existent milk, the prince decided to complete a true act of compassion and give his body to the tigress to save her life. As the tigress fed on the sacrifice, she left the prince’s bones which eventually were buried on the hill that later became the holy monument. The sacrifice and pure display of generosity is important because it explained how this trait of the Buddha was exemplified. In 1978, Khenchen Thrangu Rinpoche founded a monastery that has grown tremendously. An additional Temple was opened in December of 2008. We stayed in the monastery guest house for 4 days during my semester, which was an incredible experience. We ate every meal in the dining hall alongside hundreds of monks. We were served dhal bhat (rice and lentils) by young men with massive industrial size pots and pans while we sat amongst their peers, shoeless and silent. During the time we were there, we had lots of conversations about what monastic life was like for them, especially in such a holy site of worship. We went on guided tours where all of the symbolism of intricate wall paintings and statues throughout the massive complex of monasteries.

Additionally, I would be remiss in not mentioned Tibetan prayer flags and their role in society as we talk about representation and memory. Most people are probably familiar with the strings of multi color fabric squares, but it is such a ubiquitous part of Buddhist life in Nepal that it is important to talk about their significance. The Tibetan word for prayer flag is Dar Cho. “Dar” is to increase life,fortune, health and wealth and “Cho” translates to “all sentient beings”. Each color stands for a different element- White is air, red is fire, green is water, yellow is earth, and blue is wind. They each have a mantra on them that goes “Om Mani Padme Hum” that is a collection of values that have significance when repeated as a chain. The flags are supposed to be put up with unselfish intentions with general wishes to carry peace and compassion to all living beings. They were ubiquitous parts of my study abroad. In Humla, in Kathmandu, in Mustang, in Namo Buddha. They are an important part of Buddhist culture.